Native Bees in the East Bay

Bees are the ultimate pollinators – their bodies are covered in fine hairs that are perfect for collecting and carrying pollen from one flower to another. The pollination of angiosperms (flowering plants) is dependent on bees, and the fruits and seeds of native plants form the diet of whole ecosystems of organisms, making bees crucial to biodiversity conservation.

Bees belong to the insect order Hymenoptera, along with wasps, ants and sawflies. There are seven families of bees worldwide, with six of those families and 3500 species occurring in North America.

The San Francisco Bay Area hosts around 90 species of bees, out of more than four thousand native bee species throughout the continental United States. There are five families of bees that frequent the East Bay, and by introducing native plants into your garden, you can provide important habitat for them:

- Apidae (Cuckoo, Digger, Carpenter, Bumble, and Honey Bees)

- Colletidae (Membrane Bees)

- Andrenidae (Mining Bees)

- Halictidae (Sweat Bees)

- Megachilidae (Leaf Cutting, Mason and Cotton Bees)

Did you know?

The humble honeybee (Apis mellifera) is not native - it was introduced to North America from Europe in the 1600s.

The Western yellowjacket (Vespula pensylvanica) is a common social wasp throughout California and the broader western United States.

Bees vs Wasps - what's the difference?

Bees diverged from Apoid wasps and developed a mutualistic relationship with angiosperms (flowering plants) approximately 144 million years ago.

Whereas bees are vegetarian, collecting pollen and nectar from flowers to feed their offspring, wasps are carnivorous, hunting spiders and insects and using their stinger to immobilise their prey.

What most bees and wasps share in common is their nesting habits – the majority of bees and wasps nest below ground in burrows, with only a minority nesting above ground.

The Lifecycle of Bees

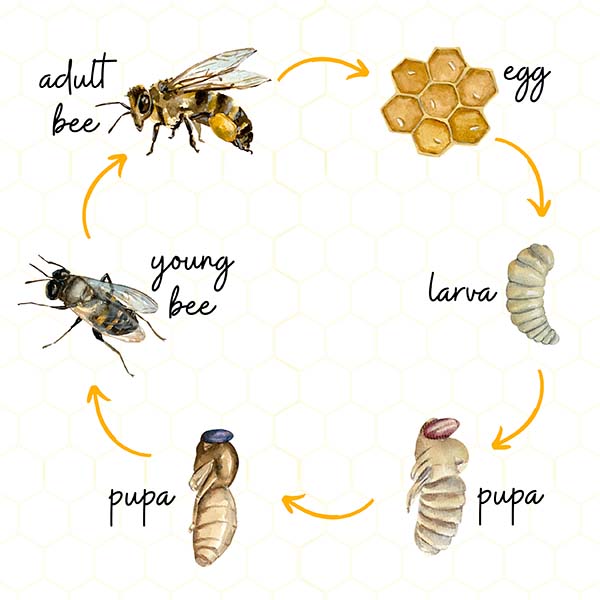

Bees undergo four stages of development throughout their metamorphosis – egg, larva, pupa and adult.

Most solitary bees produce only one generation per year and have a one-year lifecycle, emerging from their nests at the same time every year. Social bees typically produce more than one generation per year and have shorter lifespans.

Different species of bees follow a seasonal emergence phenology – meaning they emerge at different times of the year. Vernal species for example, emerge in spring when there are less plants flowering, and egg laying is complete by summer.

Did you know?

The majority of bees (approximately 70%) nest below ground in burrows, and 90% of all bees live a solitary lifestyle.

Nesting

Most people think of bees living in communal hives with a sophisticated division of labor and a queen bee that lays all the eggs. However, approximately 90% of bees actually live a solitary lifestyle, with a single female bee responsible for all the tasks that are typically carried out by many bees in a social nest. For this reason, social nests are more resilient as they are less susceptible to the many things that can go wrong and prevent a solitary female from completing the provisioning of her nest.

While the majority of bees (approximately 70%) nest below ground in burrows, there is much variation between bee genera and species in terms of nest architecture and soil type preferences. Some bees prefer sandy areas whereas others prefer dense loam or silt-loam soil. Some have shallow burrows with lateral tunnels, whereas others have extensive, deep branching nests. Ground-nesting bees construct their nests with a range of materials collected from their environment, including resin from pine trees, pith from flower stalks, leaf tissue, wood fibers, mud and plant hairs.

For the 30% of above-ground nesting bees, most rely on pre-existing cavities in dead trees, fallen logs or in soft woody branches and herbaceous flower stalks, including Sambucus (elderberry), the mint family (Lamiaceae) and sunflower family (Asteraceae).

Threats to Bee Populations

Native bees throughout North America and worldwide face serious existential threats. A combination of factors are contributing to an estimated 50% decline in the population of native bees in North America, including:

Pathogens

Some species of bees (predominantly bumblebees) are susceptible to a fungus that infects their gut, fat body and reproductive organs. The fungus (Nosemba bombi) emerged in the mid 1990s in commercially-reared bumblebee hives and spread to wild populations. The continuing use of commercially-reared bumblebees for agricultural purposes poses an ongoing risk to wild populations.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation of the Natural Landscape

As humans continue to change natural landscapes, bees experience habitat loss as diverse native ecosystems are replaced with human development or non-native and homogenous plant species. The conversion of natural landscapes, even on a small scale can impact both common and rare bee species due to a reduction in forage and nesting opportunities. The ongoing fragmentation of natural landscapes creates isolated, geographically distant habitats resulting in inbreeding as bees are unable to move between habitats. The actions of individual landowners, such as extending lawns, removing logs, clearing or changing vegetative cover and cultivating invasive plants creates an inhospitable landscape for bees.

Replacing native habitat with manicured lawn creates a "bee desert" - an environment that provides nothing for a bee to eat or nest in.

Pesticide Exposure

The widespread use of pesticides has had detrimental effects on not only bees, but all types of insects that rely on plants to survive. Plants that have been treated with pesticides uptake the chemical and express it in leaf tissue, pollen and nectar. Pesticide exposure can have a lethal or disabling effect on bees – impacting their ability to forage, fly or return to their nest.

Neonicotinoids are a type of insecticide that has attracted attention and is being reviewed for its negative effects on bee populations.

Climate Change

Changes in temperature, sea level, phenology and distribution of plants, and weather patterns are all occurring at a rate that is difficult for many plants and animals to adapt to, including bees.

Changes in the phenology of plants have the biggest impact on bees, particularly specialist bees that are reliant on a narrow range of plants. If plants that are temperature-sensitive begin flowering earlier or later than their historical average, bees can miss out on the opportunity to feed from those plants.

Additionally, climate change has been documented to impact the protein concentration of plants, with protein levels decreasing as atmospheric carbon dioxide rises. This can affect bee health as pollen is vital for larval, ovary and egg development.

Competition from Invasive Species

Introduced species, whether in the form of bees or other insects also have detrimental effects on native bee populations. These species compete with native bees for nesting sites and floral resources, help to pollinate non-native plants (thus disrupting the pollination of native plants), and spread diseases and parasites to native bees. Some introduced bee species are particularly aggressive towards native bees, taking over nests and driving native bees off patches of flowers.

While just one of these threats is enough to wipe out a bee population, it’s no wonder that bee populations are in decline as they grapple with all of these threats simultaneously.

Gardening for Native Bees

To protect bees and provide a haven for bees in your garden, there are several landscape practices you can follow to ensure that bees have access to the basics that they need to thrive:

Protect nesting sites

Survey your landscape for the presence of bee nests, whether below-ground or in the cavities of wood and plant stems. Early spring is a good time to do it, before vegetation covers the nests. If you do discover bee nests, try to identify which type of bees they are, and provide like vegetation in similar types of soil to encourage more bees to nest there. Where possible, leave logs or trunks lying on the ground where bees and other insects can make use of them. You can also use pruners to chop off plant stems, providing stubble for bees that prefer to nest in plant stems.

Plant natives

When selecting plants for your garden or landscape, ensure you plant a diverse range of native plants that cater to diverse bee populations. Consider the phenology and nutrition of your native plants – goldenrods for example (Solidago and Euthamia spp.) provide an excellent source of protein in autumn, whereas plants in the mint family (Lamiaceae) are nectar-based. Having a variety of native plants with different forms and colors blooming in continuous succession ensures that there is forage available for different species of bees at different stages in the season.

Planting locally native plants also ensures that the plants in your garden are perfectly adapted to the local conditions, and to the local native bee populations that have co-evolved with those plants for millions of years. At Native Here Nursery, we ethically collect seeds and cuttings from native plants throughout the East Bay (Alameda and Contra Costa counties), and cultivate them for sale through our nursery in Tilden Park.

Provide habitat corridors

Evaluate the land use adjacent to your garden or landscape and collaborate with other landowners to provide corridors of native plants that are likely to attract bees. This particularly helps solitary bees that are unable to fly long distances to forage for food and become trapped in a fragmented landscape. Strips of land alongside field edges, creeks, rivers, ravines or public parks are ideal for creating native plant corridors. Wherever possible, keep natural habitats intact or enlarge them, rather than replacing them with lawn.

Eliminate pesticides

Pesticides are used in both agricultural and residential settings, but should never be used purely for cosmetic or maintenance reasons. If pesticides are necessary, choose one that has low toxicity to bees and use it in the following conditions:

- When the plant is not flowering

- After sundown when bees are not active

- When beneficial insects are not present

- In favorable weather conditions to reduce drift onto neighboring plants.